Herb Simon used this thought experiment to raise one fundamental question about human nature: No matter which society we live in, capitalist market economy or socialist planned economy, we like to conduct the vast majority of our economic interactions inside those green blobs and rarely ever venture outside onto the red lines. Why?

Most of the green blobs we encounter, be it for-profit companies, non-profit organizations, or states, tend to have three things in common. They’re bounded, usually hierarchical, and — at least in theory — accountable.

Accountability is the outcome of accounting, a discipline as old as civilization itself. It’s not easy to make accounting interesting, but for now we only have to keep in mind what it is trying to accomplish: to keep track of things by recording when they change hands or when they change in value.

Ultimately this is what allows us to rent things out, to buy something but pay later or in installments, to keep track of things we own and things we owe, of claims and obligations.

While far from perfect, accounting creates the trust for investors to give money to entrepreneurs and managers, and it is the starting point for investigations — audits — when things go wrong. In summary, accounting is the base layer on which we can assemble value chains — inside the green blobs.

So it is no surprise that the first mainframe computers found a home in the basements of banks and insurance companies to do “accounting arithmetic” in the words of Herb Simon: record and summarize business transactions.

Simon himself played a major role in the next major step of turning computers from oversized calculators to decision support systems — he is still the only economics Nobelist with a Turing Award. You simply need to add two things to the original accounting triple of who owns things, who holds things, and what‘s their value: where are things and what condition are they in, to move from accounting to planning, and from value chains to supply chains.

Once you allow things to sit in different warehouses, you can think of building and storing things in different locations. Once you source things from different locations, you can think of sourcing them from different companies in different locations. We are now leaving the green blob and are stepping onto the red lines between them.

The 1960–80s were known as the era of corporate planning, fueled in no small part by increasingly powerful computers and the processes that ran on them. By the 1990s, that evolution of corporate centralization hit a brick wall, and companies started to look for ways to divest themselves of non-core activities, in a trend known as Outsourcing.

The management decision behind the outsourcing trend — should we keep everything inside the green blob or should we step out onto the red lines — is one of the most momentous decisions in corporate strategy, but it comes with an pedestrian name: the Make-or-Buy Decision.

To compress the lifetime efforts of multiple Nobelists into a tweet-length summary, make-or-buy is about solving the tradeoff between cost and control. Most big companies have struggled with this question, outsourced their entire supply chain and then brought it back in-house or vice versa at enormous costs, without a clear answer.

But while this question can be extremely tricky to answer in particular cases, the trend over the last thirty years has clearly been in the direction of moving outside the green blobs. Most of the time, the miraculous ability of markets to discover prices and reduce costs made the loss of control worthwhile.

This trend was amplified by another invention that gained widespread adoption in the 1990s: the Internet. Together they enabled what we now know as global sourcing, or globalization for short. Today we’re perfectly used to the fact that our smartphones contain thousands of components from three continents assembled across five tiers of supply networks.

One major contribution of the Internet was the emergence of platforms — a bundle of services that brings together prospective sellers and buyers to guide the whole matchmaking process from finding each other via recommender systems to resolving conflicts via recourse and reputation systems.

In the terms of Herb Simon’s extraterrestrial telescope, platforms turn a thicket of unprotected red lines into a green blob, with themselves at the center. Be it Google, Amazon, Ebay or Tinder, being in control of a bundle of market exchanges can be an extremely lucrative business.

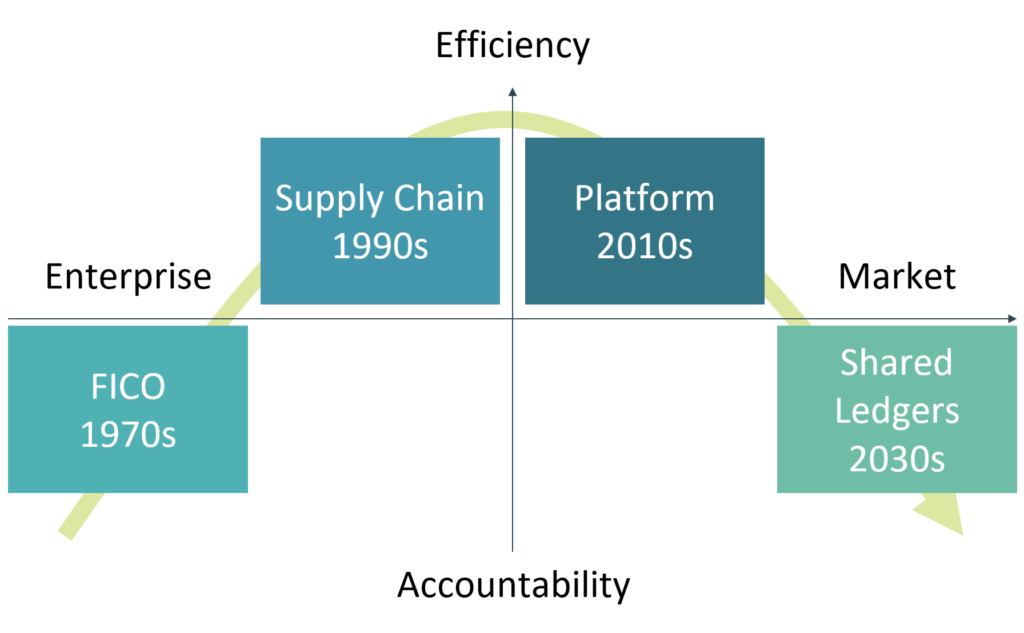

Before considering where we go from here, it might be good to summarize the last fifty years in very broad brushstrokes. If the 1970s gave us the first standardized accounting systems, the 1990s added supply chain functionality that gave us things like just-in-time delivery. The 2010s finally moved the orchestration of goods and services to the market via matchmaking platforms.

So step by step we went from corporate accountability to corporate efficiency to market efficiency. What is still missing is a way to hold markets accountable in the same way we hold enterprises accountable, but without turning them into enterprises.

In the hype phase around 2017, much has been made about blockchains as some sort of cumbersome replacement enterprise database. This is both imprecise and misleading.

The point of blockchains and shared ledgers is not to run queries and extract reports. It is about coming to a mutual agreement about what should be written into the database, and in extreme cases what should be removed. In other words, going from a single source of truth, controlled by a single entity, to a shared truth without a single source.

This is a fairly compact principle that simplifies many complexities, but it’s strong enough that it could have avoided some 90% of the unsuccessful proofs-of-concept of the 2017 era.

In the meantime, while cryptocurrencies provide a never-ending dose of daily drama in social media, a lot of teams have pushed towards the end of giving Simon’s red lines an accounting infrastructure, their work often hidden in plain sight.

Truth be told, the ecosystem is still in the phase of swarming, pursuing many wrong leads. But then again, auctions and matchmaking engines, two of the most successful building blocks of the Internet economy, took fifty years from academic research to the role they play today.

But we are seeing the first design patterns — Lego bricks that can be put together in order to build shared platforms — emerge that will allow us to finally connect Herb Simon’s red lines without turning them into blobs.

This article also appeared in Comatch Insights.